What Happens When Teams Have "Nothing to Play For"

Using analytics to determine who wants it more

On May 4, 2025, Liverpool traveled to West London to face Chelsea. The Reds held first place in the table with 82 points and also led the league with plus-48 goal difference and plus-46 expected goals difference. They had conceded more than two goals only three times in the previous 34 matches and more than two expected goals only once. Chelsea beat them 3–1 and racked up 3.1 xG including 2.3 non-penalty expected goals, both the worst numbers of the season for Liverpool. In the following matches Liverpool went 0–2–1 against Arsenal, Brighton and Crystal Palace, notching their second, third and fifth-most xG conceded of the season in those matches. In all, the Reds ended the season taking just two points from their final four matches with negative goals and expected goals difference.

Despite these seemingly shocking numbers, Liverpool’s end of season slide was not considered anything notable at the time. The win for Chelsea made a major difference in the Blues’ chase for a Champions League spot, but it didn’t matter to Liverpool. The Reds had clinched the title the week before at Tottenham. They had nothing to play for.

Famously, the difference between European sporting competition and the formats in use in North America is that in league play in Europe, there’s almost always something on the line. The teams at the bottom risk relegation to a lower league while at the top qualification for different levels of European competition remains at stake until late into the season. Only rarely does a team have more than a few weeks of matches where the points don’t matter for something.

But perhaps because there are so few of these matches, there is broadly an acceptance of the notion that teams ease up after their fate is sealed for the next season. No one asked what was wrong with Liverpool despite the obvious change in their performance level.

So this raises the most basic sort of sports analytics question. Are the intuitions of soccer fans correct? Do teams actually stop playing their best when they have “nothing to play for”? And how exactly does their play change?

What To Expect: Jonathan Liew’s Study

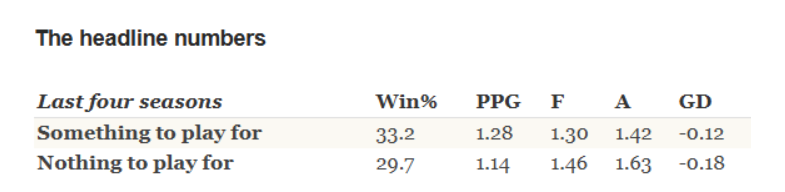

In a 2014 study in The Telegraph, Jonathan Liew identified 76 matches in the Premier League between 2010–11 and 2013–14 in which at least one of the teams involved had nothing to play for. He found that these teams did indeed play worse, taking fewer points per match. And strikingly not only did their goals conceded increase, but so did their goals scored per match. But the increase in goals conceded outpaced the increase in goals scored, leading to an aggregate decrease in goals difference.

In this study, I wanted to update Liew’s study using a larger set of data that would allow for more fine-grained analysis. It was always striking to me how intuitive Liew’s findings were, that teams with nothing to play for just stopped defending, and maybe took some more risks to attack. These results suggested that soccer players really do prefer not to defend so much, that defending is a thankless task involving hard work, focus, and putting your body on the line which players would love a chance to opt out from. And perhaps it is even the case that without the normal pressures of league football competition, players can express themselves more in attack.

The core questions here, then, are how much worse do teams play when they have “nothing to play for”, are these changes in play different in defense and attack, and do teams which have secured different places in the table, whether that means winning a title or facing relegation, show different effects from one another?

Who Has Nothing To Play For? Building the Data Set

So the first task is identifying the relevant matches. I looked at matches played in the big five European leagues starting in the 2010–11 season.1 In these league seasons, teams might have “something to play for” at many different levels.

Title. Obviously the team that finishes first wins the title.

Champions League group stage qualification. In different seasons and leagues, somewhere between the top two and top five sides might gain automatic qualification to the Champions League group stage with their finish.

Champions League playoff qualification. Teams finishing 3rd or 4th, in some seasons, have won access to the Champions League playoffs rather than directly to the group stage.

Europa League and Conference League group stage or playoff qualification. This follows the same structure as Champions League qualification for the group stages or playoffs, but takes on many different forms season to season.

Relegation / Promotion playoff. In the Bundesliga and Ligue 1 in most seasons under consideration, the top-ranked team among the bottom three in the league goes to a relegation / promotion playoff.

Relegation. The bottom two or three teams (or the bottom four from Ligue 1 in 2022–23) are sent down to a lower division.

A confounding factor is that qualification rules are fluid. Domestic cups in particular offer an alternate pathway to Europa League qualification, and when lower-placed teams win domestic cups, they can take one of the league’s qualification slots. Rather than slog through 15 years of domestic cup results to track the shifting Europa spots, I implemented a strict filter to avoid false positives. Based on the relevant league and UEFA rules, I found the places which corresponded to title-winning, Champions League qualification, and relegation, and identified the moment in the season where clubs mathematically locked in these places. I estimated the Europa qualification places based on the maximum number of places which might be given to Europa qualifiers and then excluded these places from consideration entirely. This ensures that I can be equally definitive that the final group below, teams which have guaranteed survival but cannot qualify for Europe, includes no one who could qualify for the Europa or Conference Leagues via their league position.

This method identified:

203 matches played by 63 different teams which had clinched a league title

249 matches played by 127 different teams which had secured a Champions League group stage place, as well as 15 matches played by 12 teams that had secured a playoff spot

337 matches played by 127 teams that were guaranteed relegation, as well as one team that had clinched a spot in the relegation playoff

1,115 matches played by 542 teams that were guaranteed survival in the top division but would not earn a place in Europe via their league position

Their results in these matches were easily distinguishable from their results in previous matches, to highly statistically significant degrees.