The Set Piece Revolution

The game is changing in the English Premier League.

The set piece has always been an oddity within the game of football. A sport otherwise defined by its dynamism and continuity of action on an enormous playing surface takes a break several times every match for all the players to line up and run predetermined routes into a small target zone. They have never been marginal to the sport, in recent seasons typically accounting for one in five goals scored in top league matches. But a series of questions have always hung over set pieces. Can these unusual moments be optimized and exploited for significantly more goals? If they can, will that change the entire sport? Will it be a change for the better?

As an analyst, I have watched these questions closely for several reasons. I have always had the intuition that the answer to the first two questions was “yes”, and that a skilled team of coaches and analysts could impose their ideas on the sport via set pieces to an extent that is impossible to achieve in dynamic, open-play football. Many analytics consultancies, most notably StatsBomb, have sought to develop an edge by working on set piece design.

The final reason that I have been watching these developments is that I came to soccer analytics from baseball analytics, and baseball was my first love as a sports fan. I saw the so-called “three true outcomes” take over the sport as teams, informed by analytics, realized it was a better strategy for batters to play for walks and home runs and for pitchers to play for strikeouts. The rate of balls hit into play and the amount of action on the field decreased for the simple reason that the best way to play the sport, based on the rules on the books, was not to try to put the ball in play as much. In soccer, a revolution in set pieces seems like the most obvious way that specialized analysis could change the game.

Of course, it is not necessarily bad for the game to change. A shift in strategy might lead to more goals and more excitement. Perhaps set pieces could become situations which reward clever play design that fans come to appreciate. The question, then, is what are the peculiar characteristics of the set piece moment? Which situations are being exploited to new ends, and in what ways? That will provide a more objective basis for evaluating what kind of change the game is undergoing and how the leagues should respond to it, if at all.

Set Piece and Open Play Goals in the Premier League

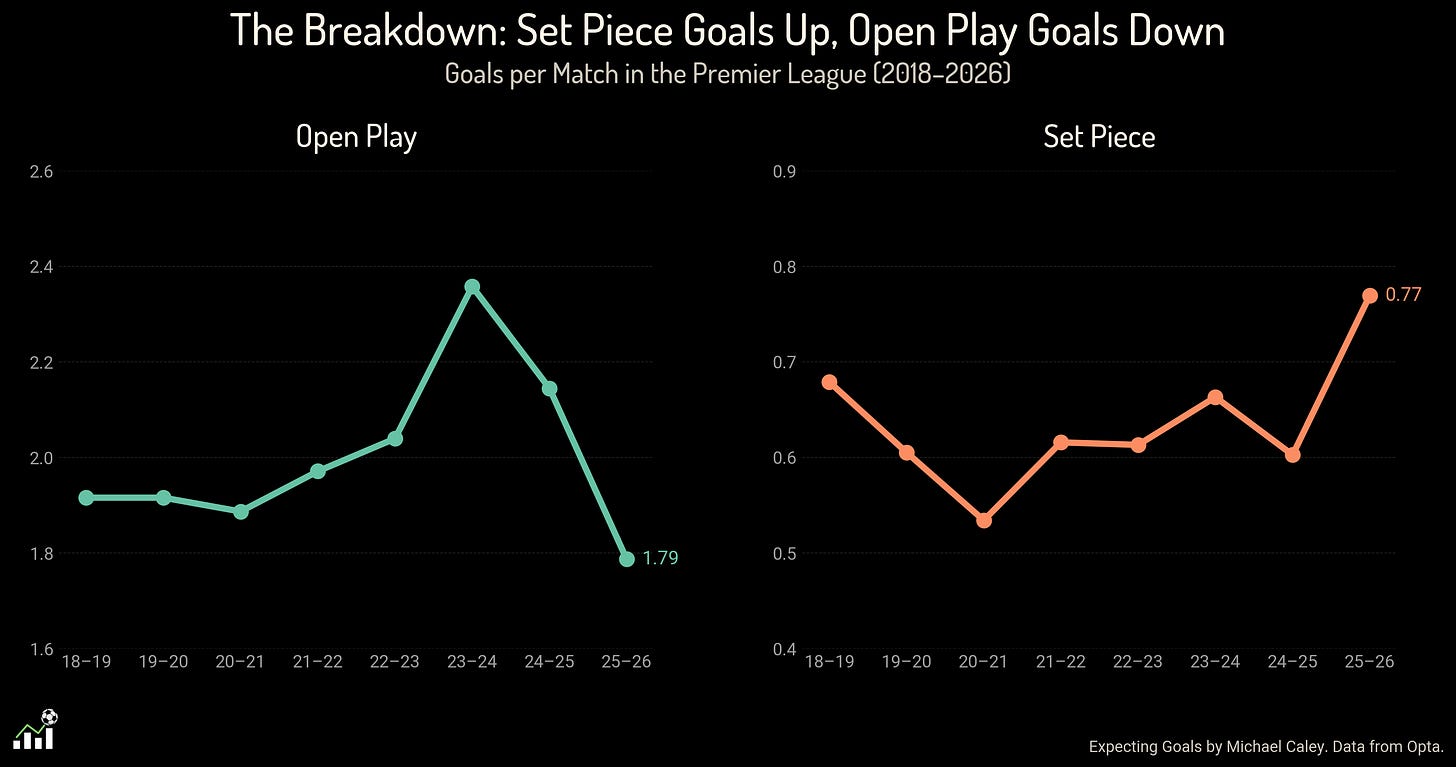

I am not the first person to notice a major shift in the composition of goal-scoring in the Premier League this season. Ryan O’Hanlon wrote about set pieces for ESPN already in October. An excellent recent article by Hamzah Khalique-Loonat at The Times extended this analysis and emphasized the same key point. Set piece goal-scoring has increased by a significant margin, and yet there have been fewer goals scored in the Premier League than in recent seasons, not more. Open-play goal-scoring has decreased by even more than set piece goal-scoring has increased.1

It is certainly intuitive that as football teams determine they can score goals from set pieces using new, optimized techniques, they will also take fewer risks in attacking possession. But this graph shows another, or perhaps a related explanation. The rate of open-play scoring in the 2020s has been significantly elevated compared to the previous decade, and so part of this effect appears to be the winding down of a short era of greater open-play excitement.

This data suggests that the drop in goals was caused by confluence of two factors: a broader defensive reaction against the high-scoring game of the early 2020s, in combination with a new emphasis on set pieces which enables less risky open-play attacking.

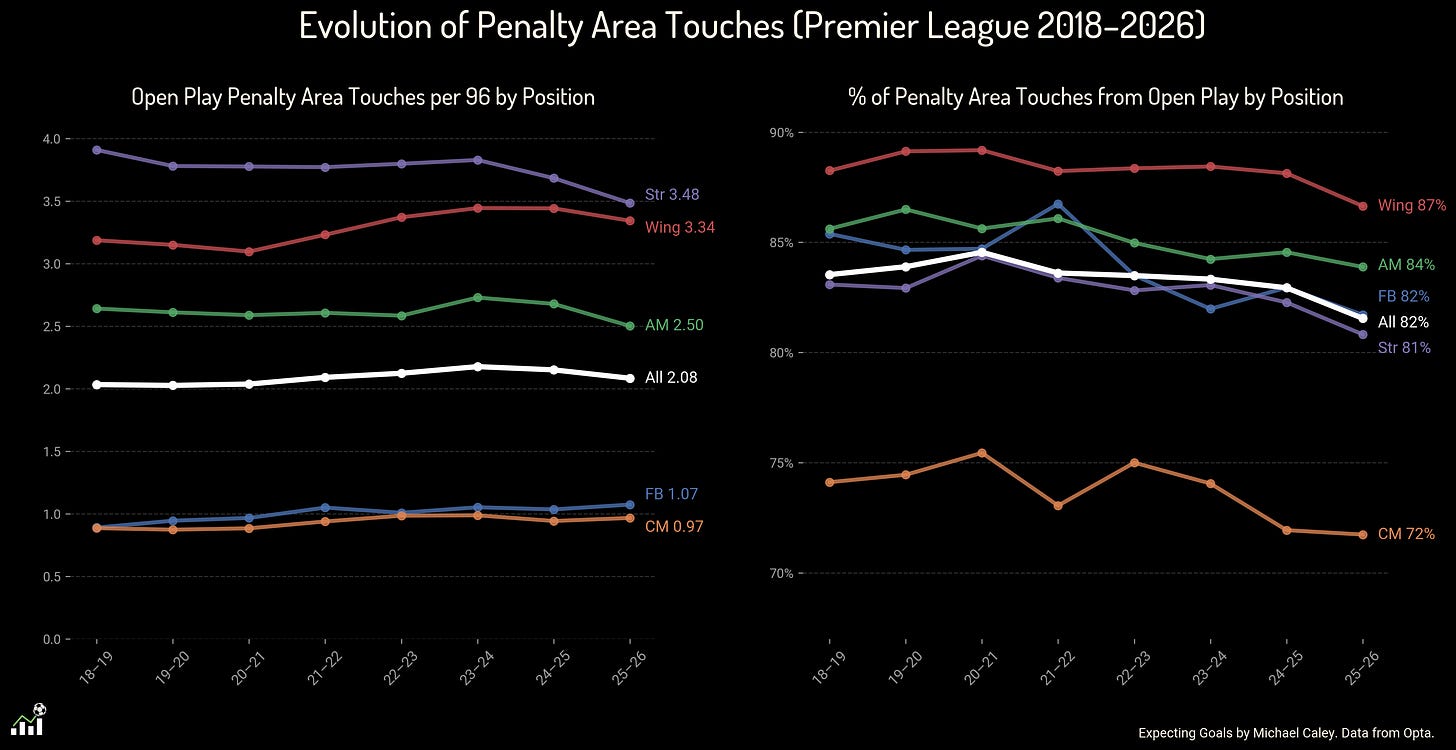

One rough estimate of attacking play is penalty area touches, and this shows a significant drop in penalty area touches for players at attacking positions from a peak in the early 2020s. It also shows that set piece penalty area touches make up a greater and greater percentage of total touches.

As Khalique-Loonat noted in another piece for The Times, touches, shots and goals by strikers are all down this season. This analysis shows that other attackers, although to a lesser degree, have also seen fewer open-play penalty area touches compared to their recent averages.

It seems likely that improvements in defensive tactics and conditioning have also made attacking more difficult, and the shift to set pieces can be understood both as a reaction to tactical trends and a cause of these trends.

But up until this point I have been talking about “set pieces” as an undifferentiated group. An analysis of the specific types of set pieces that are being exploited and the different means of this exploitation can bring to light more precisely what is happening in the Premier League this season.

Crosses and Throw-ins: A Working Theory

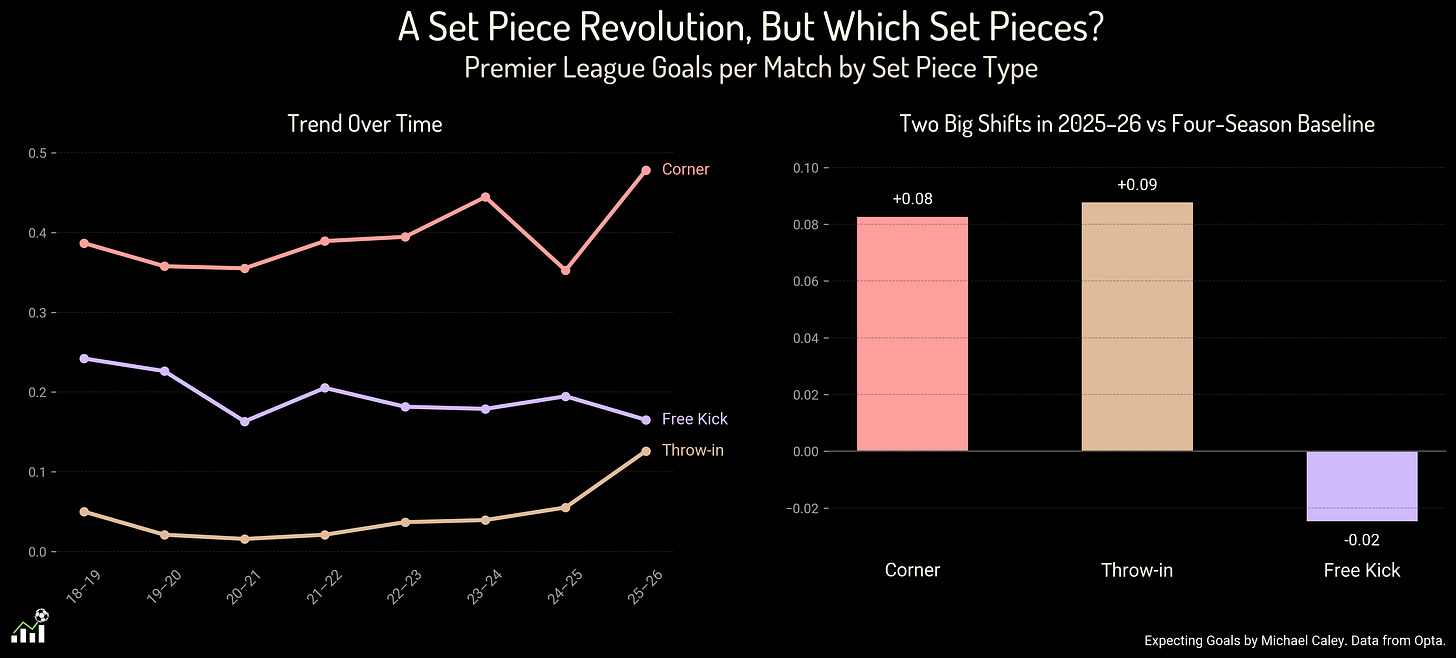

The “set piece revolution” may be a misnomer.2 The increase in goal-scoring has not come from every set piece equally, and in particular it has arisen from two unusual types of play.

Broadly, there are three types of dead balls which can be used to create set pieces.3 There are throw-ins, which can be launched into a crowded penalty area from the sideline, and corners likewise crossed in from the corner flag. And there are free kicks, a much more diverse set of opportunities spread all over the pitch which can be used for direct shot attempts, crosses, launches, or a variety of trick plays. The effects of the set piece revolution are seen entirely in the first two categories, while scoring from free kicks has actually decreased.

The long throw-in cross has been a marginal-at-best part of most Premier League teams’ arsenal for the last decade, and it has suddenly risen in importance to be nearly equal to free kicks. Corner kicks have seen more variance over time, but this season certainly marks a major new high.

It may be that these changes are unrelated, but this result suggests at minimum a hypothesis about what part of the rule book the set piece revolution exploits.

What do corners and throw-ins have in common that free kicks do not?

There is no offside rule on corners and throw-ins when they are taken.

In these two situations, unusually within the game of football, the defending team cannot determine by its shape the area within which the attacking team must play. The attacking team can then pack the penalty area with bodies in whatever formation they choose. It appears that this particular gap in the rules has been the primary opportunity identified and exploited in the Premier League this season.

If Anything is a ‘Revolution’, it is the Long Throw

There have been over 0.12 goals per match this season from throw-in set pieces. This means that in a typical weekend of watching the Premier League, you would expect to see a goal scored from a long throw. This is an increase of more than double from the 2024–25 season, which saw about 0.055 goals from throw-in set pieces, and an increase nearly four times over from the longer-run baseline of about 0.03 goals from long throws.

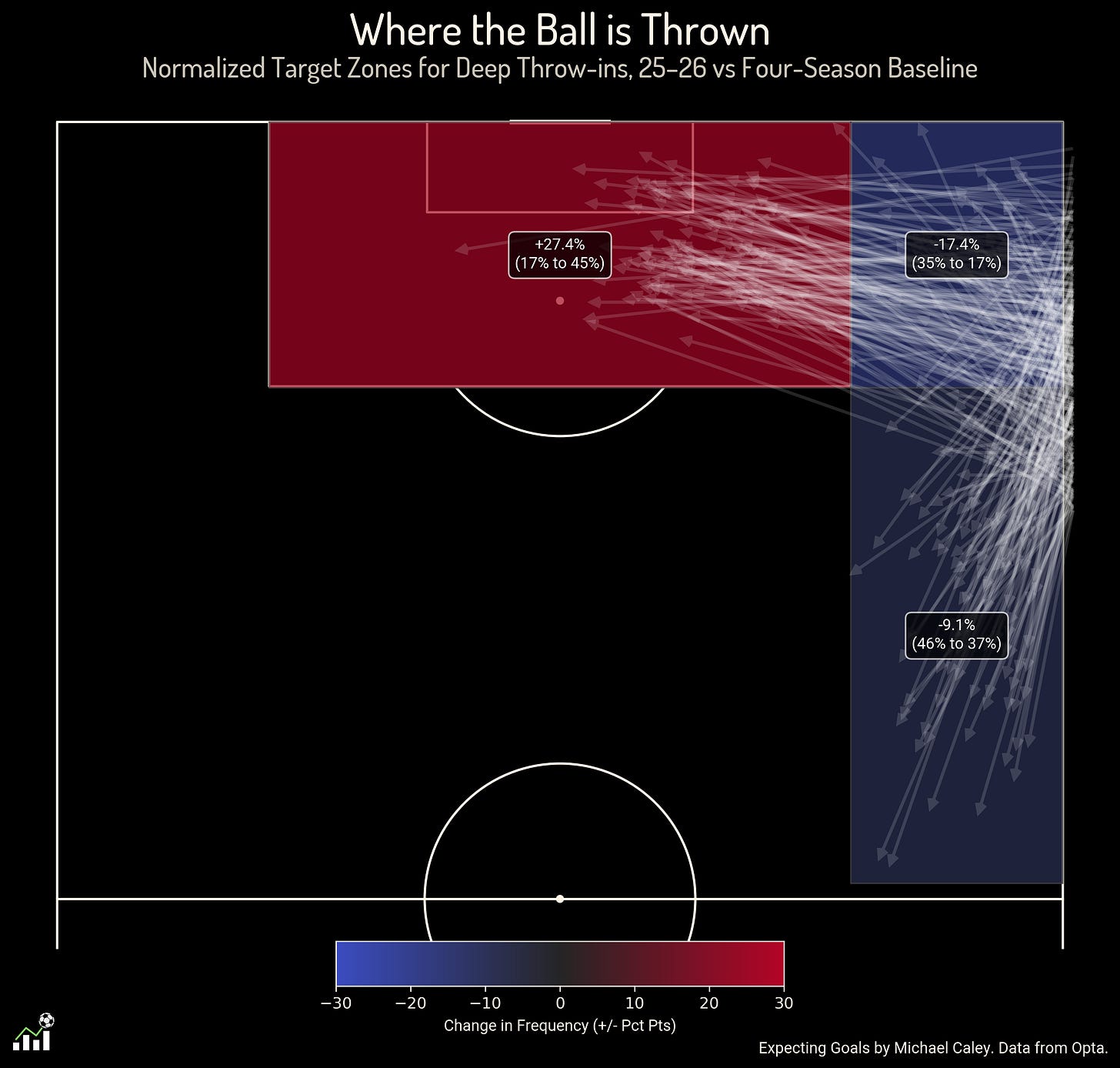

The basic explanation for this is simple. Teams play far more throw-ins directly into the penalty area than ever before.

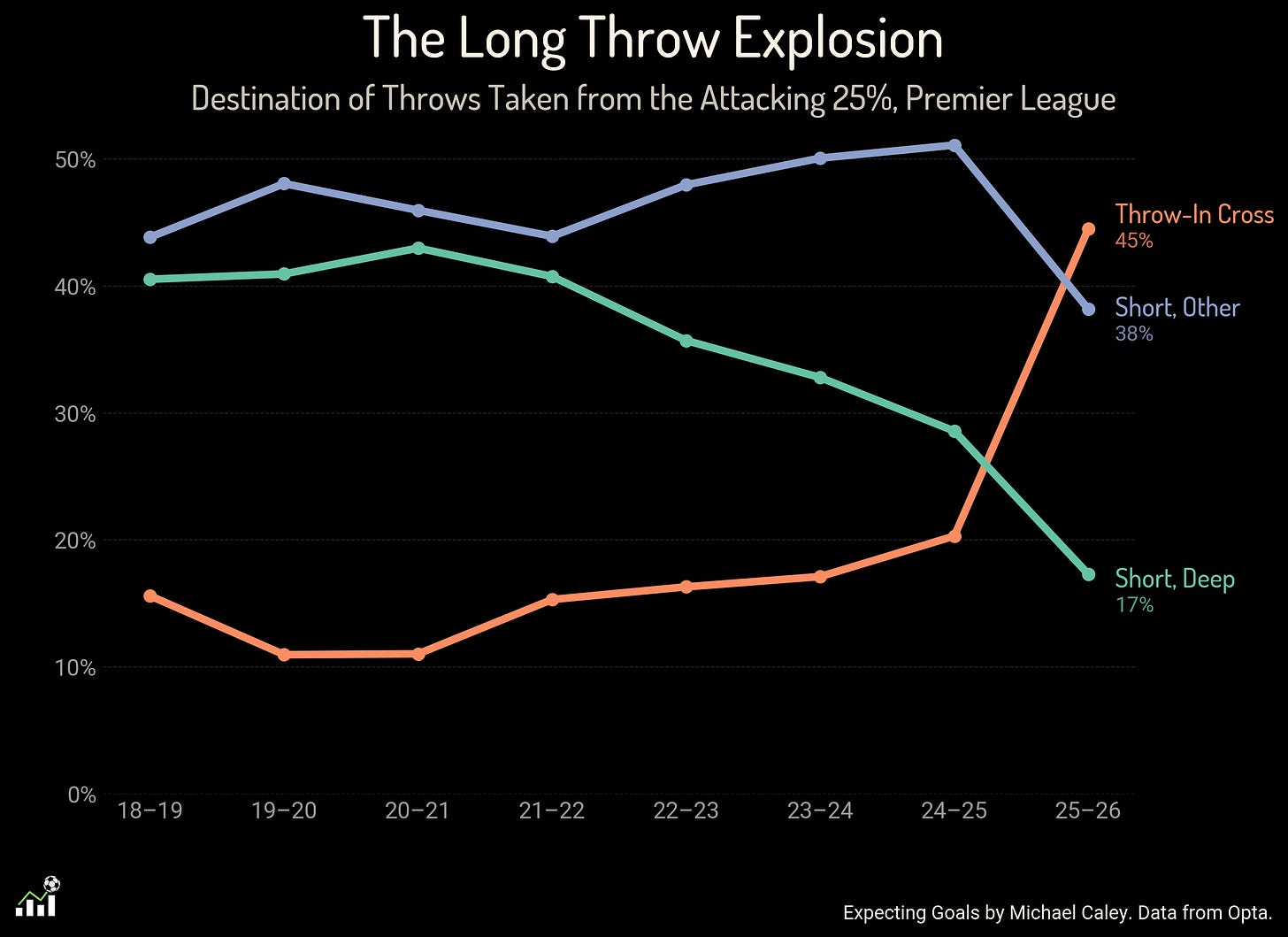

The percentage of throws taken from attacking areas directly into the penalty area has nearly tripled compared to the 2021–25 average. Somewhat fewer throws are taken backward, while only half as many are taken to the attacking wing zone.

This radical shift in throw-in strategy can also be seen from a graph of frequency over time.

While small changes were already visible before this season, the change has been truly radical. Within one season, crosses surpassed both types of short throws to become the most common play used on a throw-in from attacking areas.

This mass change in the approach to throw-ins has required a new focus on talent, as teams have identified which of their players has the strongest overhead throw. And it has required specialized work to draw up ways to turn the floated ball in the middle of the penalty area into the best scoring chance possible. But to a great degree, this is simply an opportunity that has been hiding in plain sight for years.

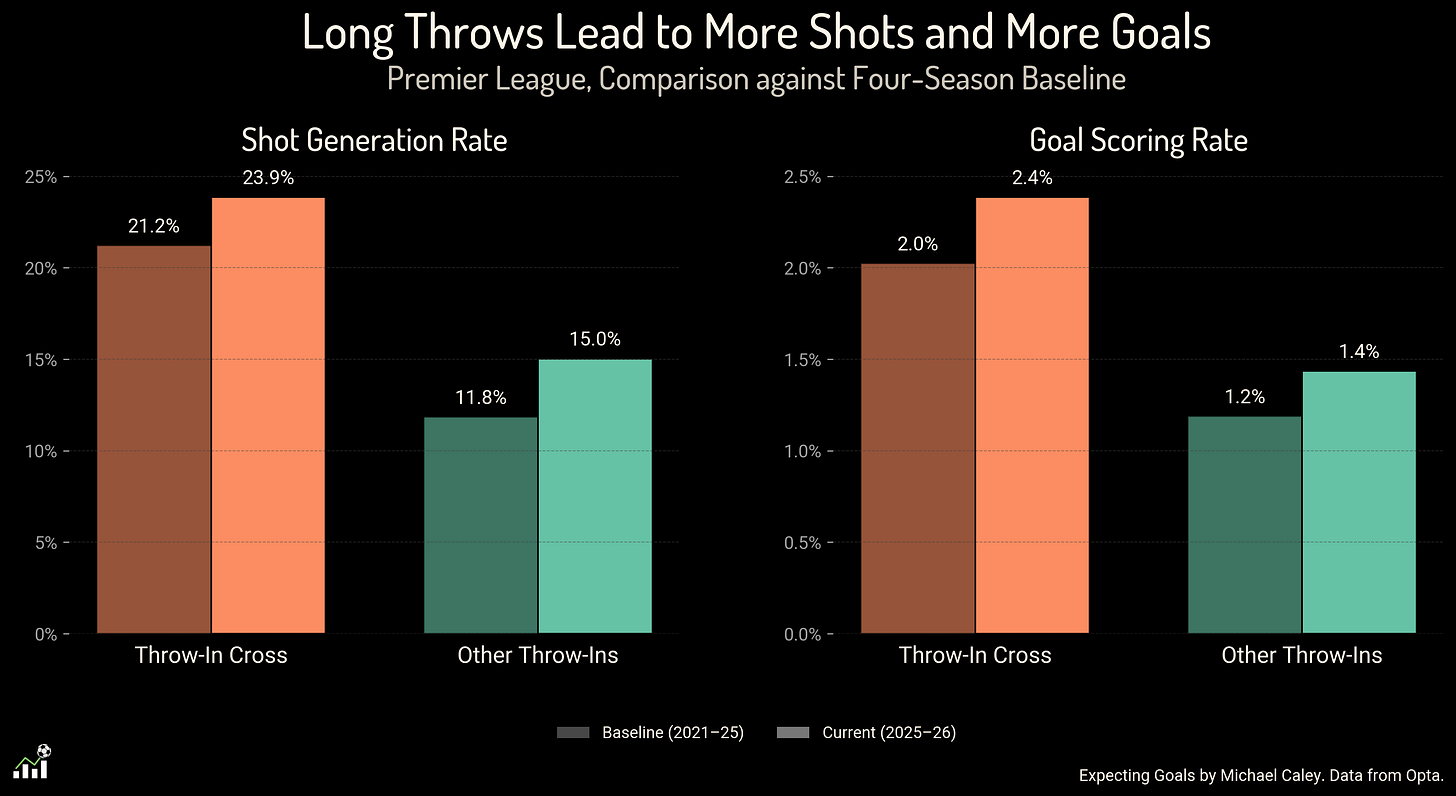

When crosses accounted for less than 20 percent of attacking throw-ins, they led to shots and goals at much higher rates than short throws. On a tactical level, it seems obvious that teams should investigate whether they can increase their usage of long throws to realize these better results at scale. And that is what has happened.

The increased tactical focus on throw-in set pieces appears to have allowed Premier League teams not only to maintain existing levels of efficiency on these plays but even to increase their production. Long throws over the past four seasons have led to shots about 21 percent of the time and goals two percent of the time. This season, even as teams have taken more and more throws long, success rates have increased, with almost 24 percent of long throws leading to shots, and 2.4 percent to goals.

Further, it is possible that the increased use of long throws has had other, positive knock-on effects. The rate of shots and goals from throw-ins taken short has increased by about the same amount as on long throws. When opposition teams have to defend the penalty area against a potential long throw, the attacking team also has the option to run other plays or simply take a short pass in for a cross.

These success rates suggest that, so long as football’s rules remain the same, teams will have little excuse for not making throw-in set pieces a core part of their attacking game. The gains cannot be denied.

Free Kicks: The Opportunities Left Behind

We know that goals from free kick set pieces have decreased this season in the Premier League. Expected goals tell a similar story, with expected goals per free kick running at about 0.12 per match compared to a past average closer to 0.13.4

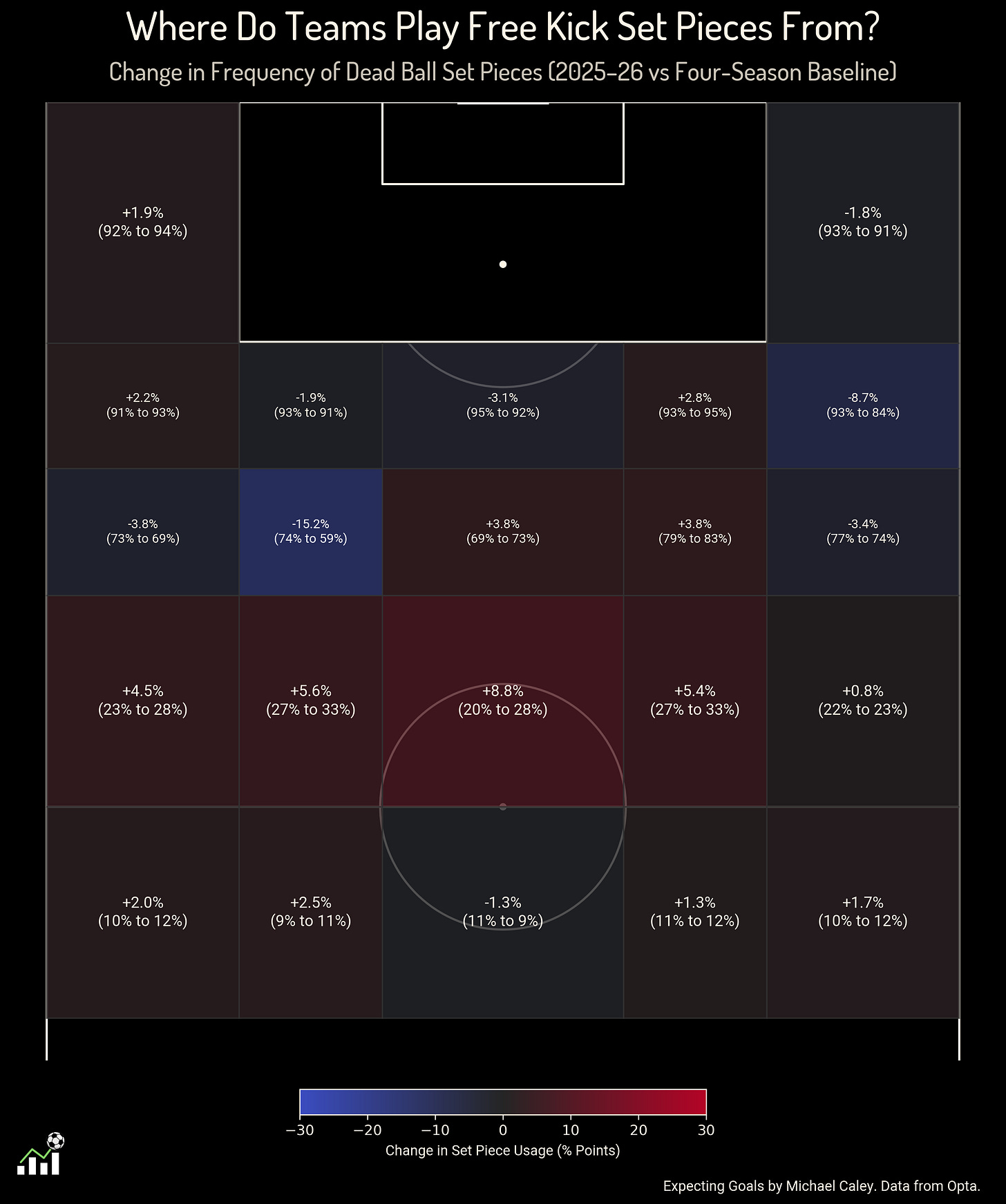

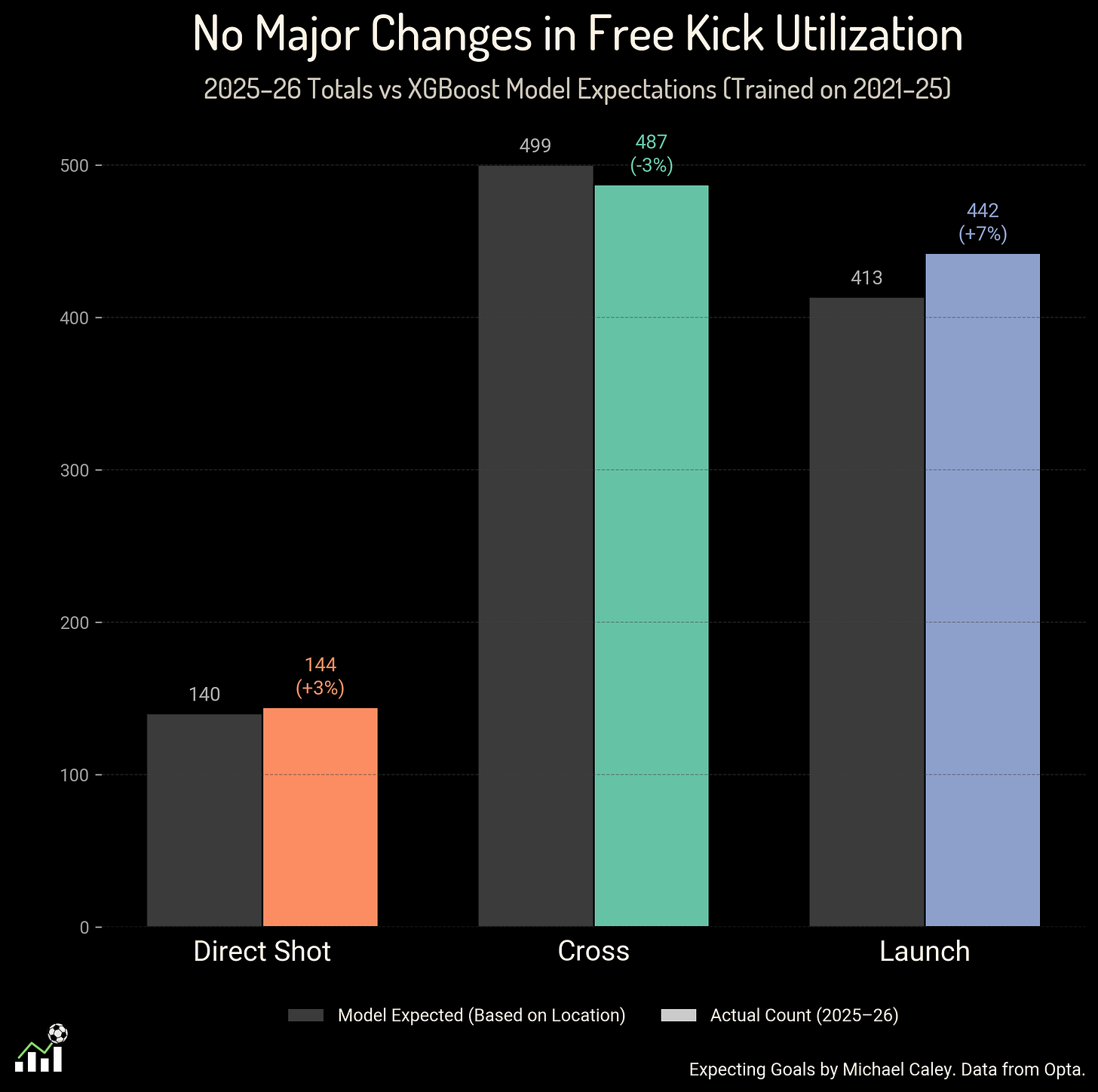

There has been a small increase in the use of free kicks as set pieces, especially from midfield, but the amount of change is much smaller than the numbers with throw-ins.

The clearest change here is a meaningful, but not enormous increase in the rate of set pieces played from central areas in the attacking half but not the attacking third. Teams are launching these balls forward more often, but not by more than five to ten percentage points. The large majority of free kicks from these deep areas are still taken short.

There are some peculiar drops in free kick set piece frequency in a few of the areas near the goal. I do not have good explanations for these zones specifically. My primary hypothesis is that teams are playing somewhat more complex set pieces occasionally, and the rules I have set up do not capture these well. One notable point about free kicks in the attacking third, however, is that teams already use these for set pieces the vast majority of the time anyway. If there were to be a large increase in set pieces, it would have to come in what John Muller has called the “Dyche Zone” of launched free kicks from deep areas.

To try to capture more precisely if free kick strategies have changed, I created a model of the likelihood of a free kick being taken as a shot, a cross or a launch. This season there have been somewhat more launches than expected, but only by a small amount.

These results suggest that there is not much room left for teams to play more crosses or shots. But the launched “Dyche Free Kick” still accounts for less than one-third of free kicks from the deepest areas of the attacking half, and only about ten percent in the most advanced areas of the defensive half. John Muller has shown the potential of these free kicks, and even in the midst of the set piece revolution there is little evidence they are being exploited to the fullest. Possibly, when teams feel they have finally maximized crowding the keeper on throw-ins and corners, there will still be more new set piece chances to create.

Corner Kicks: A Dominant Strategy

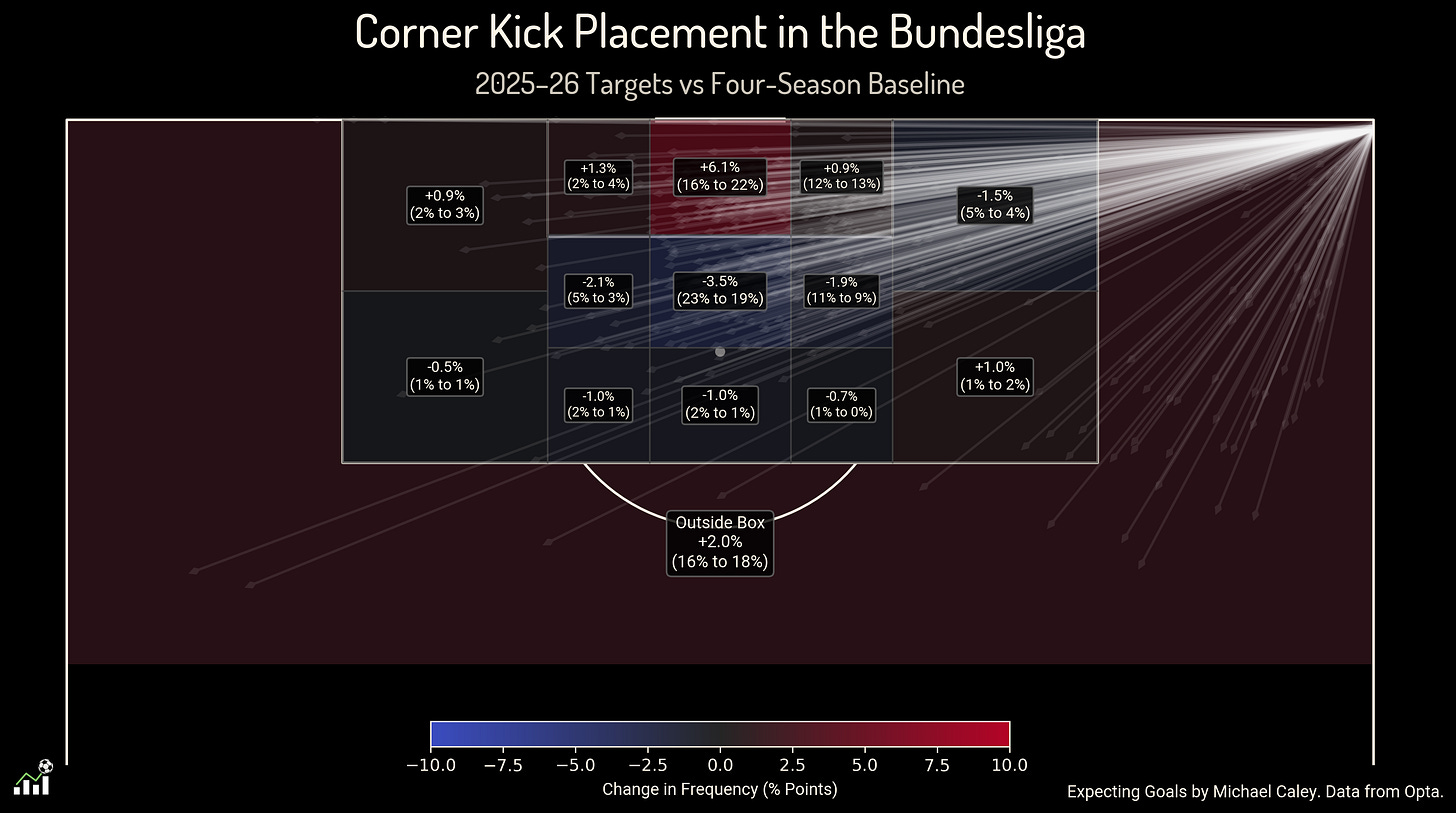

One might have thought there would not be more room to maximize corner kick goal scoring. Almost all corners are already used as set pieces and kicked long. But it turned out that there are better and worse options for corner kick placement, and significant value to be gleaned from these adaptations.

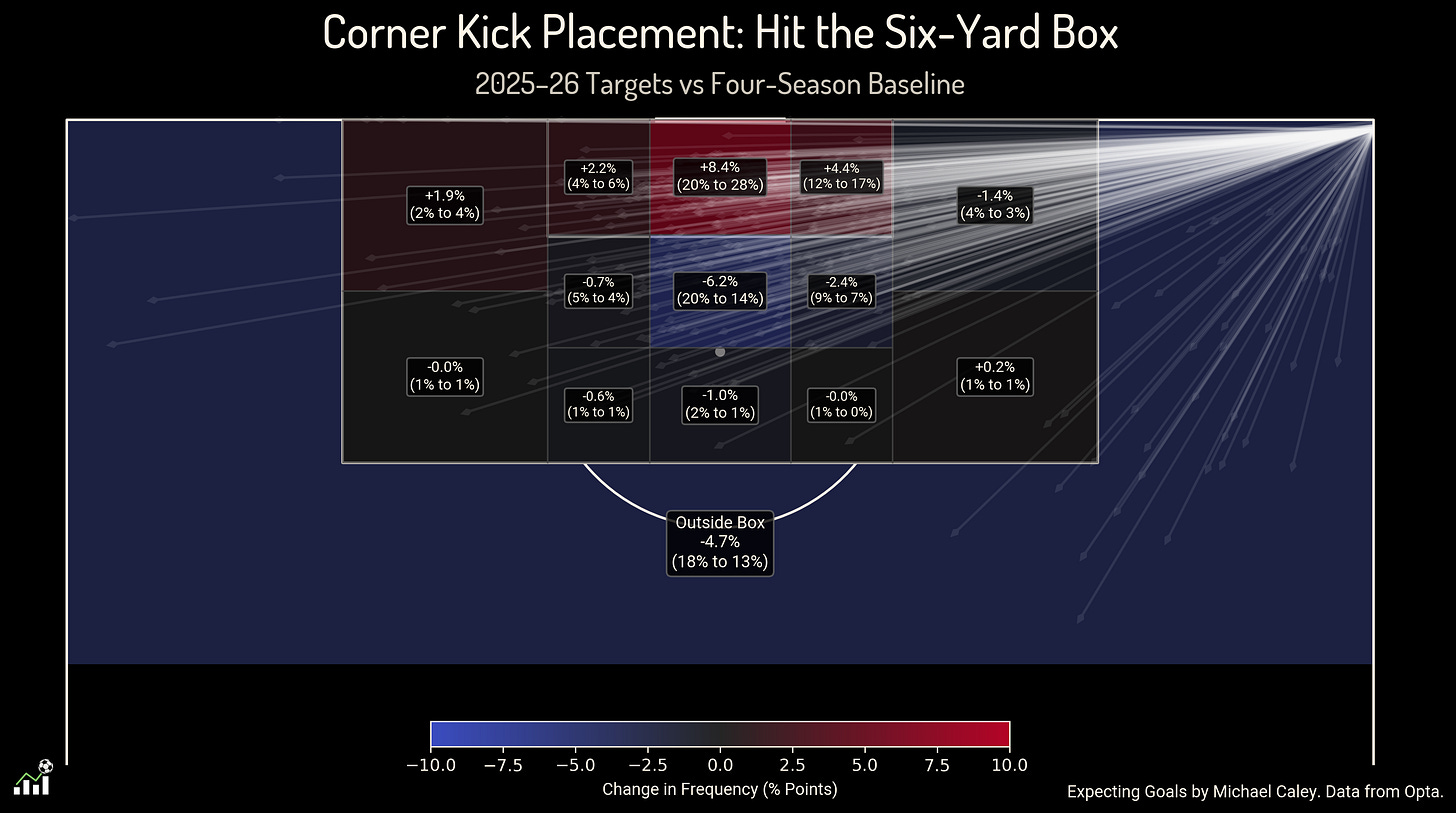

In a study for Sky Sports, Adam Smith, Nick Wright and David Forster showed that one major component of the increase in set piece goal-scoring has been an aggressive focus on in-swinging corners taken to the six-yard box. The area directly in front of the goal-mouth has been the main target, now accounting for nearly three in ten corner kicks. And that is probably only some of the corners aimed at the goal mouth, as even the best corner kick takers do not hit their spots every time.

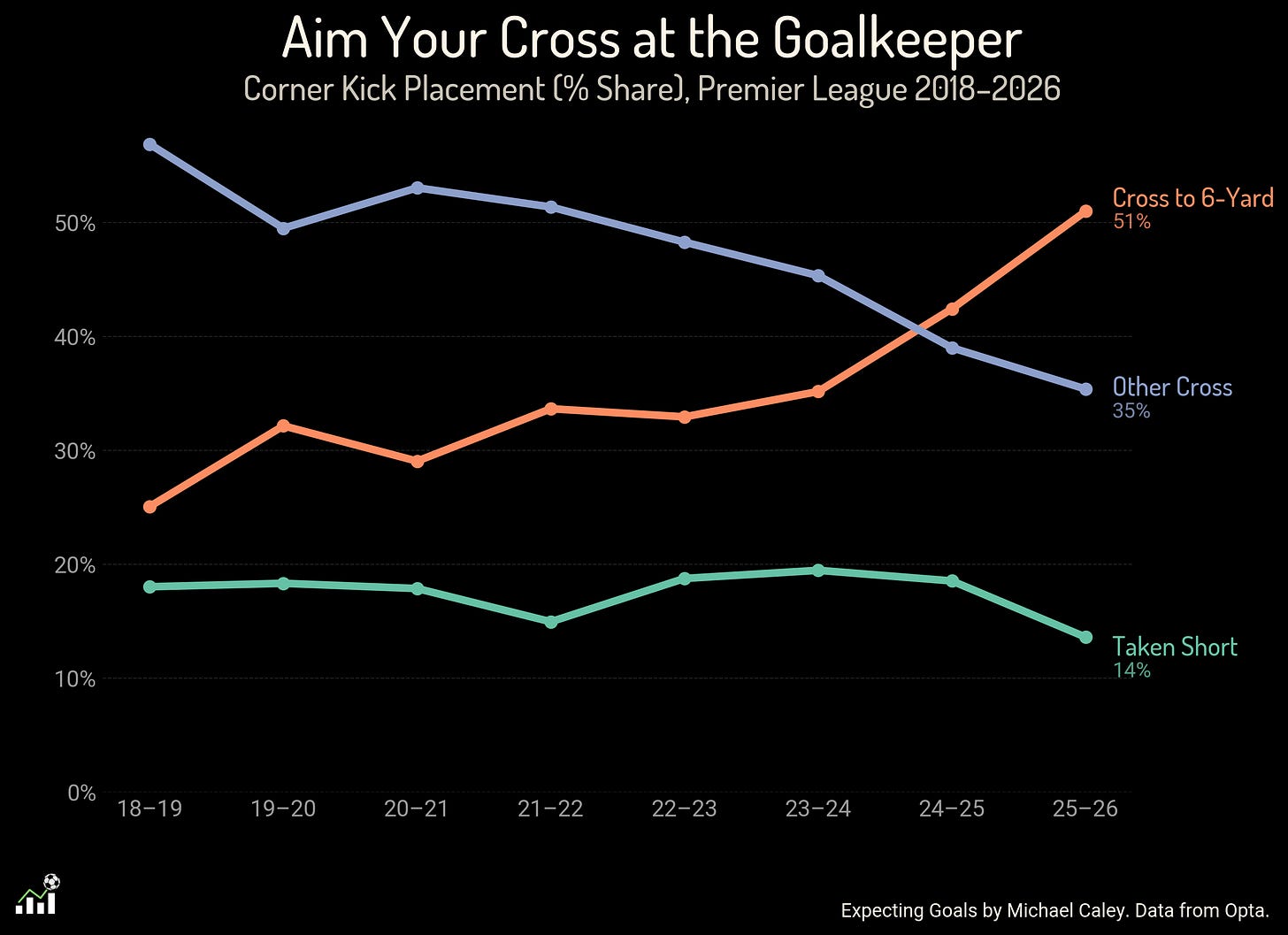

The graph of the increase in corners to the six-yard box resembles the long-throw graph for its dramatic shift, although this one does take place over two seasons rather than one.

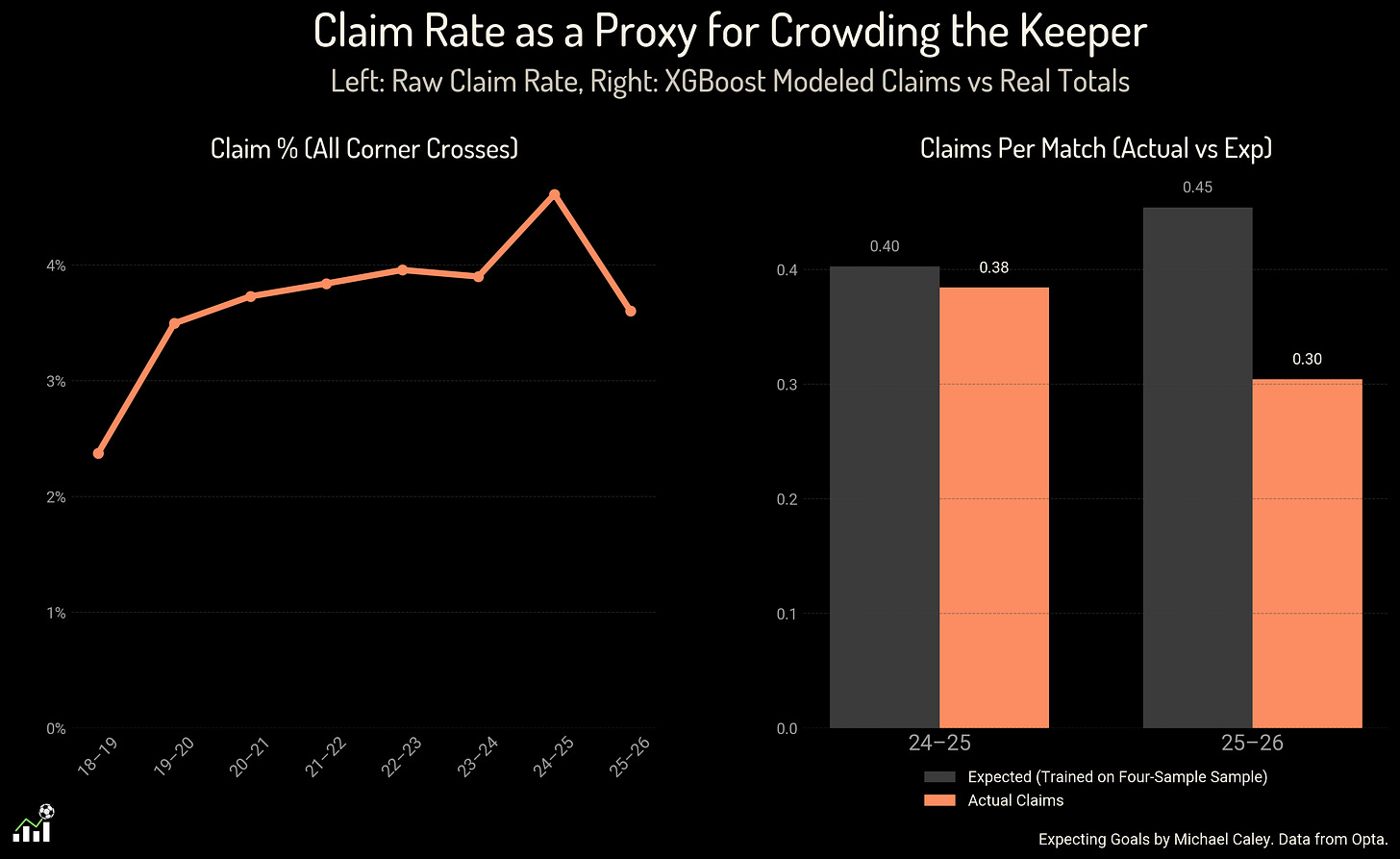

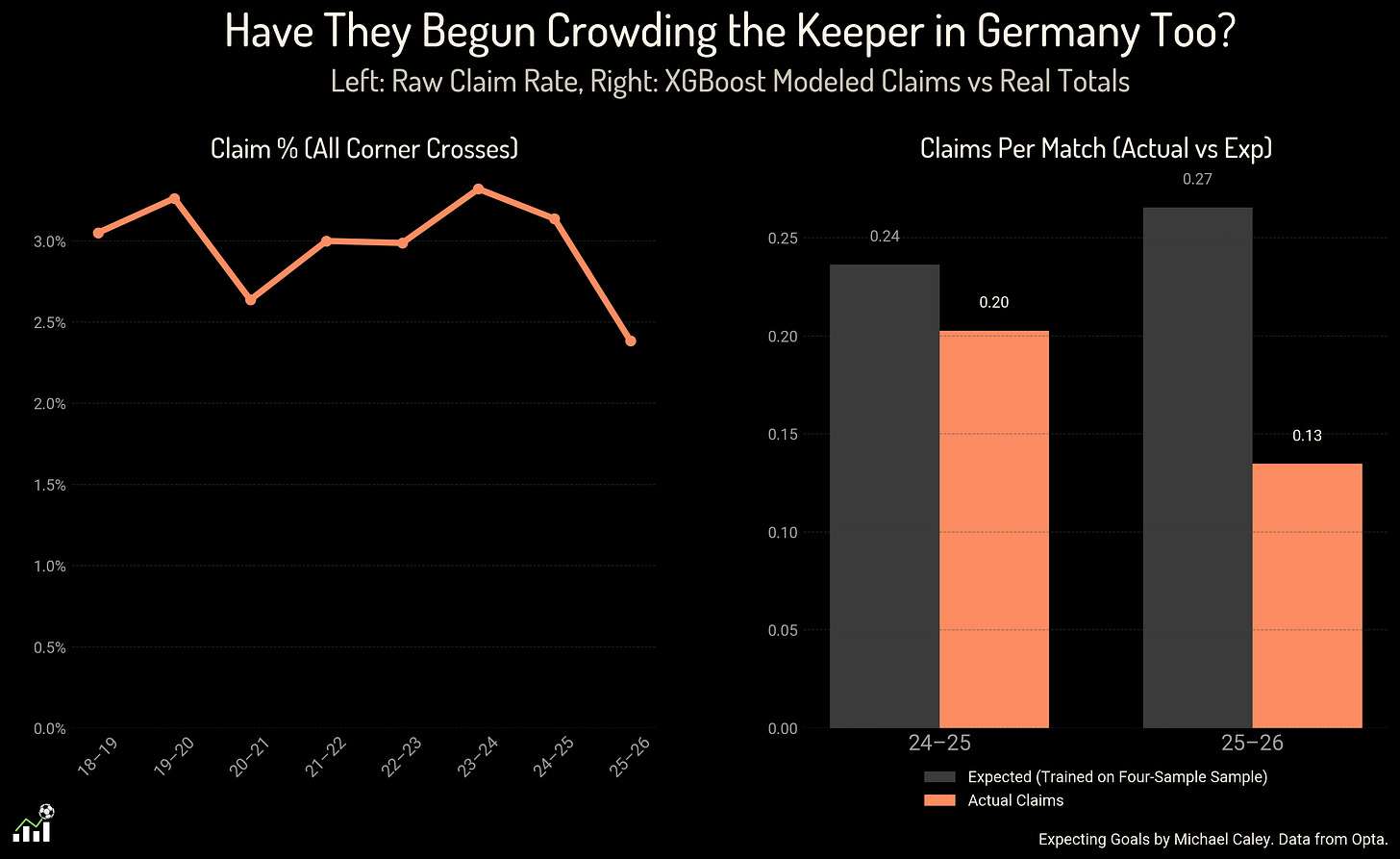

These crosses obviously target locations where the goalkeeper should be able to get to the ball. But despite this, the rate at which goalkeepers are claiming crosses has gone down in the Premier League. The current trend of surrounding the opposition goalkeeper with bodies, so they cannot patrol the area closest to goal and prevent shots from close range, is clearly working.

I built a model to estimate the likelihood of a cross being claimed, using a similar method to the free kick model, to account for the significant increase in crosses played into the vicinity of the goalkeeper. The model suggests that this season in the Premier League, keepers have been able to claim only about two-thirds of the crosses they normally would under past conditions. Strikingly, in 2024–25, the first season where crosses to the six-yard box surpassed all other crosses as the most common corner kick routine, the rate of claims also spiked and the model more or less predicted the number of times a keeper would rise to catch the ball.

It is true that keeper punches on corner kicks have increased this season, and so keepers are at least getting to somewhat more crosses than these numbers suggest. But punches are always a secondary option for a goalkeeper, which they take when they are unable to safely claim. Again, this suggests the crowding the keeper strategy is working.

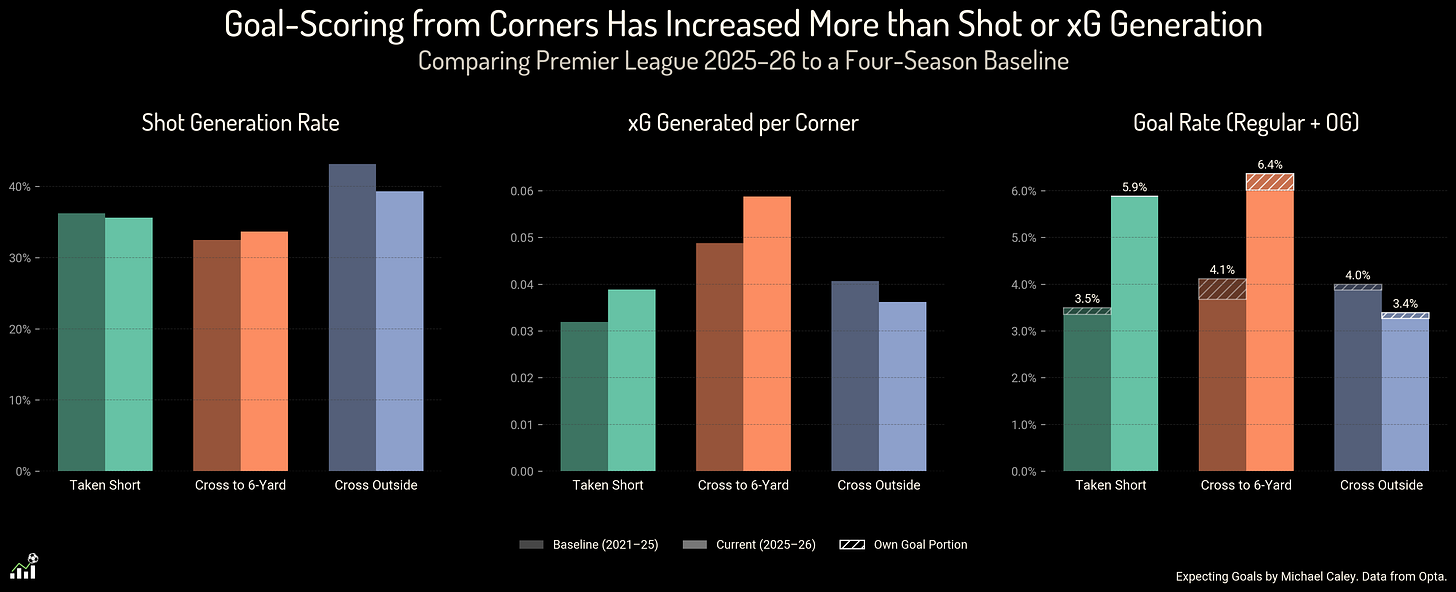

This strategy may help explain one of the primary oddities in the corner kick data. Unlike the situation with throw-in crosses, the increase in goal-scoring from crosses to the six-yard box has not been paired with an increase in shots from these chances.

Once again, I included the expected goals numbers in the hopes of explaining why so many more goals have been scored from a very small increase in shot attempts. Here, xG can offer only a partial explanation. Clearly the chances being created in the six-yard box are better than in past seasons, according to the xG model, but only to a degree that explains somewhat less than half the increase in goals scored from these shots.

Two possible explanations present themselves, both of which likely have some merit. The first is that part of the corner kick goal explosion this season has been a fluke of finishing, and the scoring rate from corners should come down to some degree. The second is that the strategy of crowding the keeper is throwing off the xG model, which was not trained on data from this tactical context.

There are two other points to draw from this graph. First is the own goal number. Own goals make up a small, but still significantly larger percentage of goals from corner kicks taken to the six-yard box than corner kicks taken to other locations. Playing a ball more or less at the goal increases the chances it will take a deflection off a defender on the way in.

Second, we see a large increase here in goals scored from short corners. The xG data suggests this is probably more of a fluke than anything else. But it seems possible again that changing the direction of attack unexpectedly, with the keeper surrounded, might also lead to benefits that the xG model is not able to pick up.

One reason I am emphasizing the importance of the tactical change of goalkeeper interference is that past data suggests aiming crosses to the six-yard box was not an obvious winner. This is different from the evidence on throw-ins where playing them long has always been more successful than taking them short. With corners, the inswinger hit to the goal-mouth only becomes a dominant strategy in combination with other changes which magnify the advantages of such crosses.

Conclusion: Looking to the Future, and Germany

Anyone who has been watching the Premier League this season could have told you that set pieces have taken over ever more of the game. This newsletter, to a great degree, serves only to confirm what your lyin’ eyes have already told you. But what is going to come next?

In his piece for The Times, Hamzah Khalique-Loonat reported that he had spoken to an IFAB official about set pieces in September and they had no concerns at the time. While some changes in the rules may be implemented, in particular a shot clock for bringing the ball back into play, I am skeptical these will make any major dent in the effectiveness of these strategies. A long throw specialist sprinting rather than jogging over to take a throw-in will save some time, but it is unlikely to make long throws meaningfully less of a dominant strategy.

What we will have to see in the Premier League is whether any tactical counterstrokes exist. So far none has arisen. It is possible that the set piece trend is like innumerable previous tactical trends, an innovation just waiting for a counter-innovation to come along and re-balance the game. But it is also possible, and it tends to be my hypothesis, that set pieces are a real gap in the football rulebook, situations where a dominant strategy exists and clubs will have few choices but to follow the trend, at least until more significant reforms to the rulebook are implemented.

If that is true, the question may not be what responses to set pieces there are, but rather whether set pieces have been fully exploited yet. In particular I wonder if launched free kicks will become a larger part of the game as teams look for new edges.

But even more than the Premier League, I will be watching the top leagues around continental Europe. If these strategies work, they will surely be picked up elsewhere.

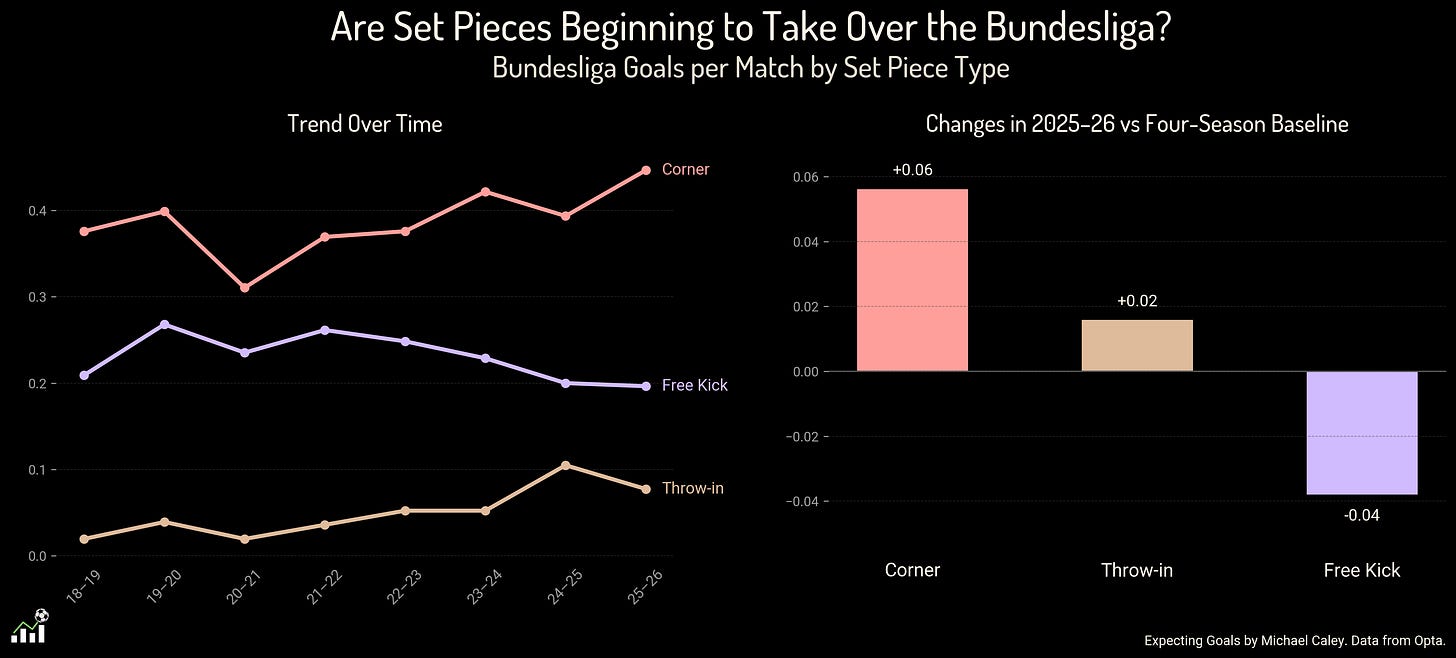

In particular, the Bundesliga shows signs of its own tactical shift to set pieces.

While the increase in goals from throw-ins this season is small, that is because the long throw had already peaked last season. The rates of goal-scoring from long throws in the Bundesliga in 2024–25 and 2025–26 are the two highest of any league since 2010–11 other than the Premier League this season.

On corner kicks, the data points in the same direction.

Goals from corner kicks are up in the Bundesliga, and crosses hit to the goal-mouth have increased significantly. Nearly 40 percent of corners are being placed in the six-yard box.

This appears to also correlate with a decline in keeper claims, although it is worth noting that Bundesliga goalkeepers are far more reticent to claim crosses at baseline.

Watching matches in the Bundesliga, I have noticed several teams making use of recognizable Premier League strategies around the goal during corner kicks. I would love to hear from more dedicated German football fans if this trend is something they have noticed as well.

One of the theories of the Premier League’s set piece revolution has been that Premier League refereeing standards are a core factor. The idea that goalkeeper “should be stronger” when he is blocked by a wall of bodies from reaching the ball is certainly common in English commentary. It may be that refereeing norms which are kinder to keepers elsewhere will limit the effect these tactical trends. It is also possible that refereeing standards simply have not been stress tested yet, and there is more room to make use of physicality, or just masses of human bodies, in the continental leagues as well.

What the Bundesliga data suggests is that it is already happening, and it is already succeeding, if to a lesser degree.

I am by no means certain that the set piece revolution has only just begun. Any number of dynamic responses, from defensive adjustments to national norms of play and refereeing, could prevent the continuation of these trends in England or their extension to other football leagues. At the same time, corner kick and long-throw tactics have been adopted and demonstrated their effectiveness in the Premier League with remarkable speed. At this rate of spread, top football leagues across the world could see rapid shifts in goal-scoring and tactical trends within the year. I am particularly interested in whether this summer’s World Cup will crystallize these trends for an even larger audience.

There is every chance that the set piece revolution has only just begun.

Appendix on Method: Defining “Set Pieces”

Identifying which situations can be identified as set pieces begins as the most basic football question and eventually develops into an irreducibly uncertain quandary that can only be resolved with some best-guess heuristics.

Obviously when a player plays a dead ball cross into the center of the penalty area and their teammate heads it home, that’s a set piece goal. If a player launches a long throw into the penalty area and it isn’t cleared and in the chaos a defender kicks it into the net, that’s a set piece goal. But there are two important edge cases. The first is, when does a dead ball play constitute a set piece? How far does the ball need to be kicked or thrown to start a set piece action? And second, when does a set piece end? If a ball is cleared out of the penalty area but recovered by the attacking team and they cross it in again during the second phase, is that still the same set piece?

For this analysis, I made the following choices.

All corner kicks constitute set piece opportunities even if they are taken short.

Throw-ins are counted as set pieces when they are thrown into the penalty area, or when the data is tagged as a “throw-in set piece” by the provider, indicating that the action involved a designed play aimed at creating a good shooting opportunity within the next couple touches.

Free kicks are counted as set pieces when they are taken directly as a shot, played as a cross, or launched at least 20 yards and into the central area of the pitch, either into the penalty area or a region about eight yards extended beyond the penalty area. Likewise, when an action is labeled as a “set piece” for some other characteristic not immediately visible in the on-ball data, that will also count the action as a set piece.

Further, I chose to count second phase opportunities within the same set piece action. A “second phase” ends when the possession itself ends, either with a turnover or a dead ball, or when the ball is recycled into the defensive half of the pitch, or 20 seconds elapse from the initial playing of the dead ball. These definitions mean that my numbers may differ slightly at the margins from other studies, but they clearly accord with the findings of others in broader terms.

If you are wondering about the technical specifications here, and exactly which shots and goals can be defined as coming from set pieces, you can check the Appendix on Method at the end of the newsletter. No growth-hacker has yet identified a better way to sell a subscription newsletter than with appendices on method.

sadly the Substack architecture does not allow me to go back and change the newsletter title after I have written it.

Perhaps in time someone will determine a way to consistently produce shots from goal kicks. A bright future awaits us indeed.

For the most part, I have avoided using xG in this newsletter. With hundreds of matches of data, we can be reasonably confident that most xG variation will even out. Further, I am concerned that an expected goals system built on data from a different era of set pieces might fail to capture the quality of chances created. So I will use xG to check possible errors but not depend on it.